This is something I’ve been reflecting on recently. At work, we often rely on surveys to measure how engineers feel, but I’ve realized we sometimes give too much weight to them.

I think we need to put company surveys into context; in this case, I’ll focus on the surveys we run within our group of software developers.

Take this example: 70% of respondents from a survey of 250 engineers say the development environment is too slow.

It’s tempting to conclude that engineers are unhappy with how the environment works and that we need to take immediate action, even changing the architecture if necessary.

But when reading this example, we might have overlooked whether 250 is really a large enough number. This leads to the next question: how big is “big enough”? It’s well known that the larger the sample, the better it represents the population. What if it were 2,500? Or 25,000? Or even 250,000? Would the data carry more weight?

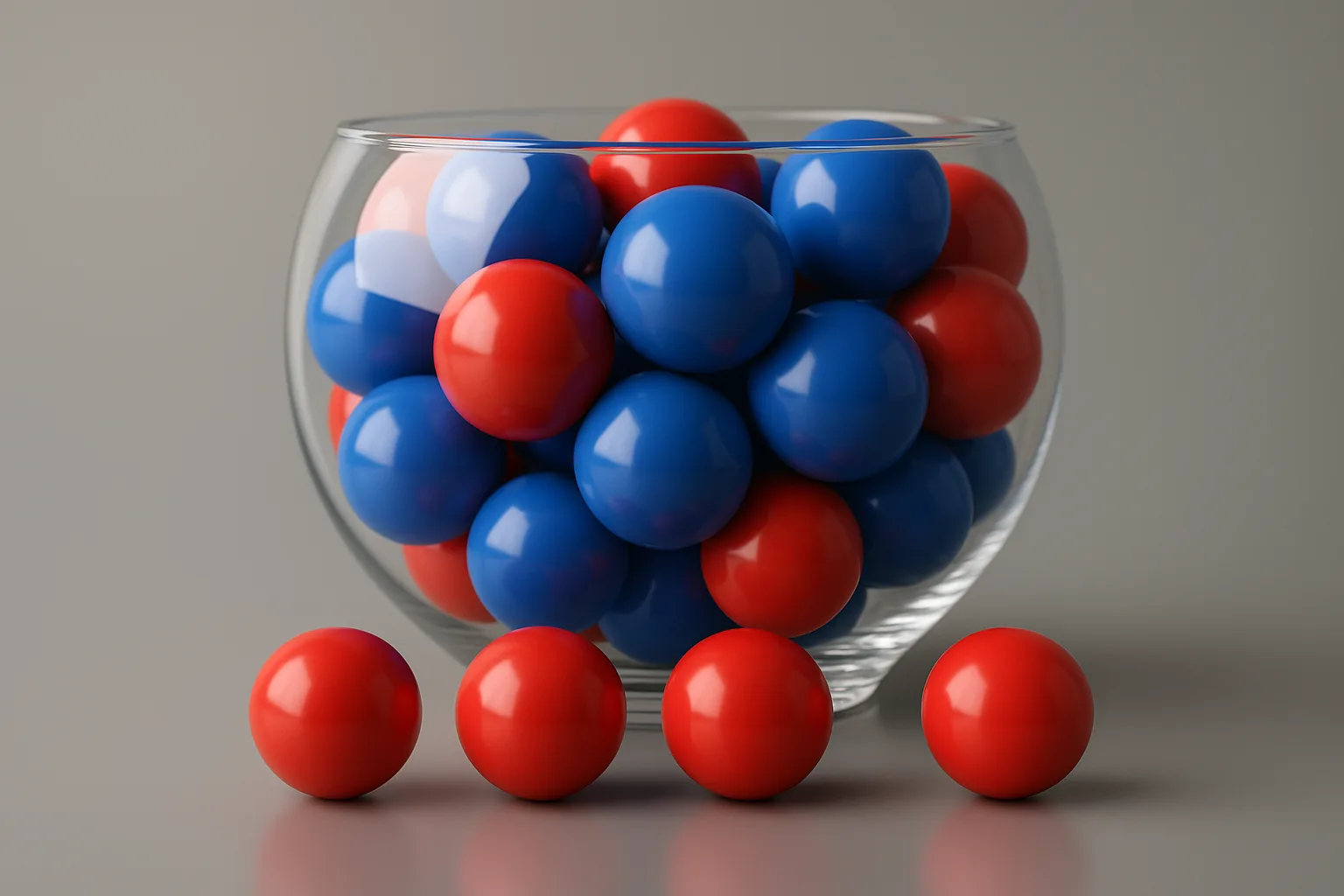

Let’s pause for a moment and imagine a jar filled with red and blue balls (assuming roughly half red, half blue). We draw 4 at random, count the colors, and put them back in. How often do we end up with all the balls the same color—either all blue or all red? If we increase the sample to 7, the probability drops from 12.5% to 1.56%. It’s exactly the same population; we just took a larger sample. Small numbers magnify extremes and noise, making it much more likely to see patterns that don’t represent the whole.

Unfortunately, the responses from surveys within a company are usually quite limited and therefore more vulnerable to noise. Suppose all 250 of our engineers respond—which rarely happens—then we’d have the full population. Even then, each individual carries a lot of weight: every person represents 0.4% of the overall result. If 10 people share a strong negative experience, the outcome can shift noticeably without reflecting the rest. Even with a full-company survey, the population itself may be small enough that outliers skew results disproportionately.

That’s why these surveys should be treated as noisy signals—smoke that needs interpretation, not an immediate call to action. They’re most useful as long-term trends, where we can ask whether there’s really something behind them.

So, the next time you send out a company survey, think about what noise you’re really trying to measure.

References

- Daniel Kahneman – Thinking, Fast and Slow

Introduces the “law of small numbers,” showing how people overinterpret patterns from small samples.